Nearly two dozen states and the District of Columbia have committed to slashing greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, with several planning at least an 80% cut.

Some Democratic presidential candidates are outlining goals for the majority of electricity to be decarbonized within the next two decades.

But how big a lift will that be at the state level?

State agencies and private research firms are only beginning to produce specific numbers — and fuel debate — about whether the scale of the electricity and transportation infrastructure build-out required to dramatically reduce carbon emissions across the economy by midcentury is feasible.

In the case of New England’s six states, one measure of the challenge can be counted in terms of “Walneys” and “Solar Stars.”

One refers to the Walney Extension, the largest offshore wind farm in the world, which is a forest of 87 towering turbines in the Irish Sea off England’s west coast. It opened in September 2018 with a capacity of 659 megawatts, power enough for 600,000 homes in Britain.

The biggest U.S. solar farm is Solar Star in Southern California, covering four times the size of New York’s Central Park and producing a peak output of 579 MW in full sunlight.

For all the New England states to reach targets of an 80% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, generally from a 1990 starting point, electricity output may have to double to charge electric vehicles that must fill the streets and to replace gas heat with electric heat pumps, according to an analysis last year by the Brattle Group consultancy.

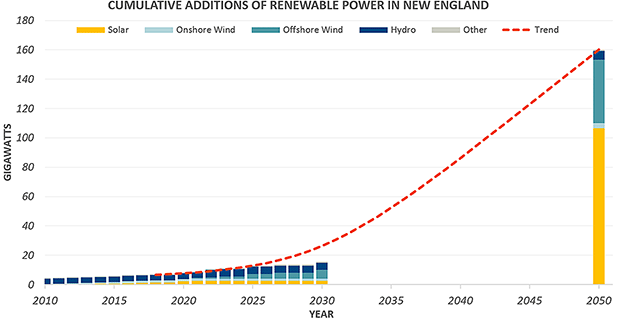

The region’s generating capacity — now just over 31,000 MW — would have to soar to 160,000 MW, mostly through wind and solar, in one of several future scenarios Brattle calculated.

That’s the equivalent of four Walneys and six Solar Star projects a year for the next 30 years in New England.

The idea of replicating those two projects again and again on an assembly line track for decades defines one view of the clean energy summit New England and the rest of the U.S. could have to scale.

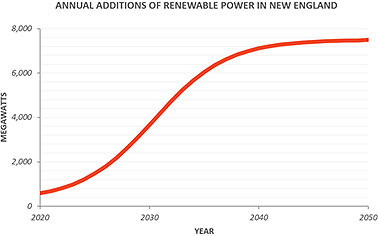

“On the other hand — and the message we are trying to emphasize — the challenge means growing the annual deployment of wind, solar and batteries by about 10% a year,” Weiss said. That growth rate has been met globally by wind power installations and surpassed by solar investments, the study said.

“If New England keeps growing these new industries at roughly the current rate, the region may have a chance to achieve the commitments made to decarbonize our economies by 2050 and do its part to reduce the risks of catastrophic climate change. And, in the process, it will create a substantial and sustainable new green economy,” the Brattle group reported.

But the Brattle study is just one bookend in the debate surrounding the costs and infrastructure involved in decarbonizing the grid.

“I think we’re just on the cusp of a new wave of questions that are emerging that have to be answered,” said Emil Dimanchev, senior research associate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research.

“How do we actually build a power system that is mostly wind and solar? We’re just starting to look at this, and there are a lot of unanswered questions about how we get there and get there cost-effectively, as well,” said Dimanchev.

Another study, which focused on California, found a more economically feasible path forward, although it did not track the exact timelines and scenarios as the Brattle study.

That analysis from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the ClimateWorks Foundation last month found that California could mobilize investment, research and public support to remove increasing amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, helping create a carbon-free economy by 2045.

The cost was estimated at $8 billion a year, or nearly 4% of the proposed California budget for 2020-2021. Under less favorable assumptions, the cost could get to $30 billion annually, the study authors said.

The state would still have to add investments in new zero-carbon power plants, power transmission and distribution lines, and EV charging infrastructure.

The new plan would collect greenhouse gas emissions from landfills, dairies and wastewater treatment plants; remove hydrogen from the emissions for sale as fuel; and transport the CO2 over new pipeline networks to centralized sites for underground storage.

In addition, some of the CO2 removal would be achieved through direct air capture — pulling massive amounts of air through processing machines to chemically extract CO2.

“It was a welcome surprise to see how reasonable the costs appear compared to other studies,” said Sarah Baker, staff scientist at Lawrence Livermore and lead author of the report. “We were pleased.”

‘Urgently needed’

[+] The chart illustrates one scenario for how fast renewable generation — mostly offshore wind power and solar units — would have to grow to achieve New England’s low-carbon emissions goals for 2050, according to a Brattle Group study.

National polls indicate that while public concern over climate change is widely shared, an understanding of future costs of climate action is not.

Roughly half of Americans believe action is “urgently needed” in the coming decade to avoid the worst effects of climate damage, according to a Washington Post and Kaiser Family Foundation poll in November. But only four in 10 were willing to make “major sacrifices” in response.

Three-quarters of poll respondents said they would oppose a 25-cents-a-gallon tax on gasoline to combat climate change threats, only half of the tax on carbon emissions that some leading economists argue would be needed to tilt the economy away from fossil fuels toward zero-carbon alternatives. Against that background, Americans are headed into the 2020 presidential campaign with Republican and Democratic parties diametrically divided on the climate issue.

New England states and others that have aggressive clean energy goals are just starting to calculate the costs of their climate commitments and speak to ratepayers and voters about what that may mean.

In Massachusetts’ case, David Ismay, then a senior staff attorney with the Conservation Law Foundation, wrote last year, “While we know that achieving net zero by 2050 is technically possible, we also know it won’t be easy. There’s no ‘silver bullet’ policy or single program that can do it all or save us from having to make some hard decisions over the next 30 years.”

Ismay — now undersecretary for climate at the state’s Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs — has the assignment of producing draft pathways this year for achieving Massachusetts’ pledge to cut carbon emissions by 80% by 2050.

“For Massachusetts, questions about costs are a year too early,” said Caitlin Peale Sloan, senior attorney at CLF and Ismay’s former colleague.

New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy (D) issued a master plan last month intended to eliminate carbon emissions in the state’s energy sector by 2050. Estimates on the costs to ratepayers are to come later this year, officials said. Rutgers University professor Frank Felder warned that the transition would be “expensive and regressive” and predicted a “substantial increase” in residents’ energy costs (Energywire, Jan. 28).

New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, enacted last July, requires utilities to rely on renewable energy for 70% of the electricity supply by 2030 and to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions from man-made sources in the state by 2050.

Rich Dewey, president of the New York Independent System Operator, the state’s grid operator, said the organization’s top planning priorities this year include how to meet requirements of the climate act and the prospect of a surge in power demand if a large transition to EVs and electricity-based heating happens (Energywire, Jan. 23).

Analysis Group Inc., a consulting firm, in a report last October noted that because of the newness of the act, comprehensive estimates haven’t been done. “Wind’s share of total generation rose from 1 percent in 2009 to 3 percent in 2018. This offers an important perspective on what is to come. The Act calls for unprecedented increases in renewable generation in 11 years so that renewables provide 70 percent of consumers’ needs.”

While analysts can estimate the amount of clean energy that state policies require, cost estimates are a moving target, analysts agree, because renewable energy continues to get cheaper.

In Brattle’s calculation, the annual investment in wind and solar power needed to meet New England’s goals must spurt from nearly 600 MW installed next year to six times that amount in 2030.

“This is not an easy lift by any stretch. The total dollars are quite significant,” Weiss said.

The offshore wind example

The Energy Department’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory pegs the current capital costs for offshore wind resources at between $4 million and $6 million per megawatt of capacity, including turbine, platform, electronics, transmission lines to shore and onshore costs.

If 3,000 MW of offshore wind projects were going up off New England today, with an average cost of $4 million per megawatt for a completed project, according to NREL, the cost would be $12 billion.

But NREL projects that cost per megawatt of offshore wind will drop steadily to between $2.5 million and $3 million, with the increasing size of turbines and the benefits of large-scale manufacturing providing the largest benefits.

“There are excellent opportunities to drive costs down” with offshore wind, “driven by competition, by scale and innovation,” said Kevin Knobloch, president of New York OceanGrid LLC, which seeks to build three offshore transmission networks to gather and deliver 7,500 MW of offshore wind to New Jersey, New York and Massachusetts between 2027 and 2030 to meet state goals.

General Electric Co. is building 12-MW wind turbines, he said. “It wasn’t so long ago it was 2-3 MW. We’re seeing a lot of interest from the oil and gas industry supply chain, the companies along the Gulf of Mexico that build offshore oil and gas rigs and maintain them.” Companies building rigging vessels and laying pipelines see opportunity in offshore development, he said.

Addressing climate change means the new plants will have to be built much sooner.

But there is another critical figure to add to the calculation, or the cost of doing too little, too late, says CLF’s Peale Sloan.

“First of all, we are already seeing impacts of climate change on air conditioning bills in summer and damage to homes in storms.” Based on the global studies that have been done, and understanding our weather and geography, people can’t afford not to act, Peale Sloan said.

Brattle’s Weiss said he believes the projects can be built. “If you told any industry — including solar and offshore wind — the annual demand for your product is going to grow at 10% per year for the next 30 years, do you think you would have many industries that would say, ‘Oh, my God, that’s not possible’?

“In terms of the pure industrial capacity, to build the supply chain, the windmills and solar panels — that is feasible from the supply side,” he said.

Charlie Smith, executive director of the Energy Systems Integration Group, which brings experts together to tackle future grid issues, said: “I think it is starting to dawn on people that something is going on, even the skeptics. People are starting to realize the cost of doing nothing is much greater than doing something.”

ESIG’s agenda centers on how to make future power networks work with large amounts of renewable power. “Resource adequacy [of power generation] is a top one, for when the ‘sun don’t shine and the wind don’t blow.’ How do you assure you have sufficient resource adequacy to meet the load?

“If society wants to decarbonize and move to a low-carbon future, it’s our job to help figure that out because we’re good engineers.”